For the last two days, I was visiting schools in the Udalguri district of Assam. At the start of this year, my organization, Sunbird Trust, partnered with a donor to begin a project in Udalguri. As part of this project, we had to identify six schools in the district and work on improving their infrastructure. Since we had limited knowledge of the area, we approached the Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) authorities to suggest suitable villages and schools. The BTR team recommended six schools and their respective villages.

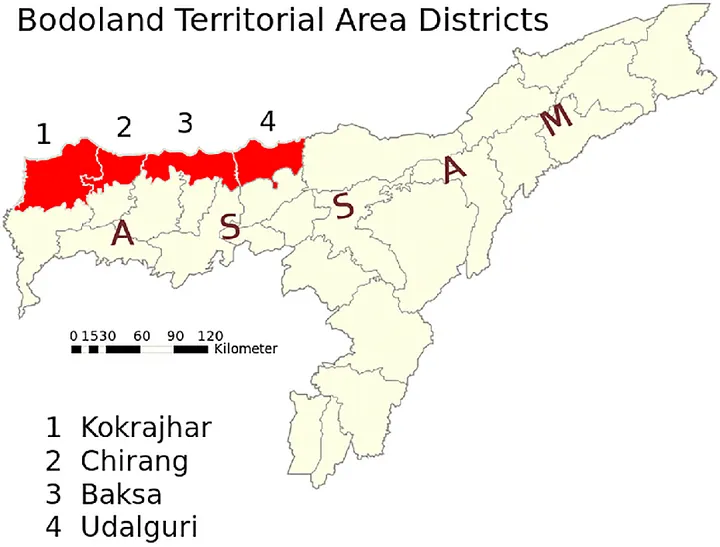

“The Bodoland Territorial Region is an autonomous division in Assam. It comprises four districts: Kokrajhar, Udalguri, Baksa, and Chirang. After prolonged violence and loss of lives in the struggle for autonomy, an agreement was signed in 2020 granting legislative, executive, and administrative autonomy under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. The area is predominantly inhabited by the Bodo tribe, who speak the Bodo language. The Bodos are recognized as the largest tribal group in Assam.”

This is the first time Sunbird Trust has taken on a project in Udalguri, and having a reliable support system was crucial to get started. We took our first steps with the support of the BTR team and also hired a local team member for the project.

Since January 2025, I have been actively learning more about the region, its people, and the scope of the project. Our implementation work began in March. By now, I’m familiar with the six villages, have some understanding of the area’s demographics, and our team has completed a comprehensive needs assessment to understand the schools’ requirements.

The implementation is well underway. We have installed street lights in all six villages, set up 2kW solar grids in each school, added street lights on school campuses, and provided water harvesting systems and fencing for school compounds. Additionally, all schools have received computer and printer systems, and new toilet blocks have been constructed.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

I finally visited Udalguri on 21st May to see the progress of the work. As I reflect and try to make sense of our decision to take on this project, I find myself delving deeper into understanding its impact. I now feel more assured that our decisions were right and feel satisfied by the small but meaningful support we have provided.

All our project locations are just a few kilometers away from the international border with Bhutan. On the first day, we visited two schools on my team member’s motorbike. Luckily, the weather was pleasant after nearly a week of rain. We left around noon, post-lunch. The ride was bumpy in parts, and I realized I was feeling sleepy — I was even scared I might fall off the bike. I’m not usually a midday napper; maybe the bumpiness was lulling me to sleep?

At one point, we had to cross a river on the bike, and my ever-so-smart brain decided to wear shoes. I was worried about them getting wet, stinking, and all sorts of other possibilities. Pranjip was confident he could cross the river without any trouble. Seeing his confidence gave me some, too. But both of our confidences took a hit when the bike got stuck in the middle of the river. I somehow managed to take off my shoes while still sitting on the bike and threw them onto the sand. Together, we pushed the bike and eventually got it out.

We visited Kalajhar and №1 Kundurbil villages and their respective lower primary schools. The head teachers were waiting for us. As we entered the villages, Pranjip excitedly began showing me the street lights. I interacted with the head teachers and the SMC chairpersons at both schools, and they expressed their gratitude. It’s common for schools to appreciate donors, but alongside their thanks, they also shared a few more needs — such as a water borewell and fencing to protect the schools from elephants. I want to further understand the real challenges faced by the community.

While we had planned to visit three schools in the Udalguri block, the rain gods had other plans. We had to return after visiting the second school.

On the second day, we visited four schools in Bangurum, Thulungjhar, Nonke Samrang, and №1 Tankibosti villages. Three of these schools are in the Bhergaon block, which is further inland. The contractor responsible for construction at all these schools also decided to visit that day to meet his masons and oversee the last phase of pending work. He brought his car, and we rode along with him.

We passed through lush green tea gardens. Some women were busy plucking tea leaves, while others were having lunch along the narrow roads.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Realities of the Ground — Observations and Discussions

All these schools are understaffed, with only 2–3 teachers appointed. The majority have just two teachers — a head teacher and one assistant teacher — to teach students from Classes 1 to 5. Each school has 30–40 students enrolled, which is considered a good number for government schools in rural areas.

With a new government policy, any school that has fewer than 30 students enrolled for 2–3 consecutive years will be shut down and merged with a neighboring school. As a result, all schools are striving to maintain a steady enrollment of 30 or more students. However, none of the schools have enough classrooms to accommodate five grades, nor do they have sufficient toilets. The head teacher and staff do not have a separate office; teaching-learning materials (TLMs) are scattered everywhere, classrooms are merged, and toilets are either dysfunctional or kept locked in an attempt to maintain them in good condition. What kind of magic was I expecting from a rural, remote school?

When I asked how they manage the mid-day meal, the head teacher and assistant teacher showed visible disappointment. Under the revised Mid-Day Meal Scheme — now called PM Poshan — the government allocates Rs. 6.19 per child per day for lower primary schools. While schools are provided grains from FCI godowns, they must buy lentils, condiments, vegetables, and oil within that Rs. 6.19.

From an economics-of-scale perspective, schools with only 30–40 children simply cannot afford to provide nutritious meals at this cost, let alone nutritious, even regular meals become difficult. In 2021, when the revamped scheme was introduced, the government’s messaging focused on not just providing food, but nutritious food. It’s a great marketing strategy to call it “Poshan,” but does that reflect in the actual practice?

The cooks are paid a meager Rs. 1,500 per month to prepare meals. Irregularities are creeping in from every corner. In social audits conducted in Assam, many discrepancies were found in the implementation of the mid-day meal scheme. In villages that are remote and difficult to access, procurement costs are significantly higher, yet the budget allocation remains the same as for urban areas. Isn’t this a clear disconnect from the realities on the ground?

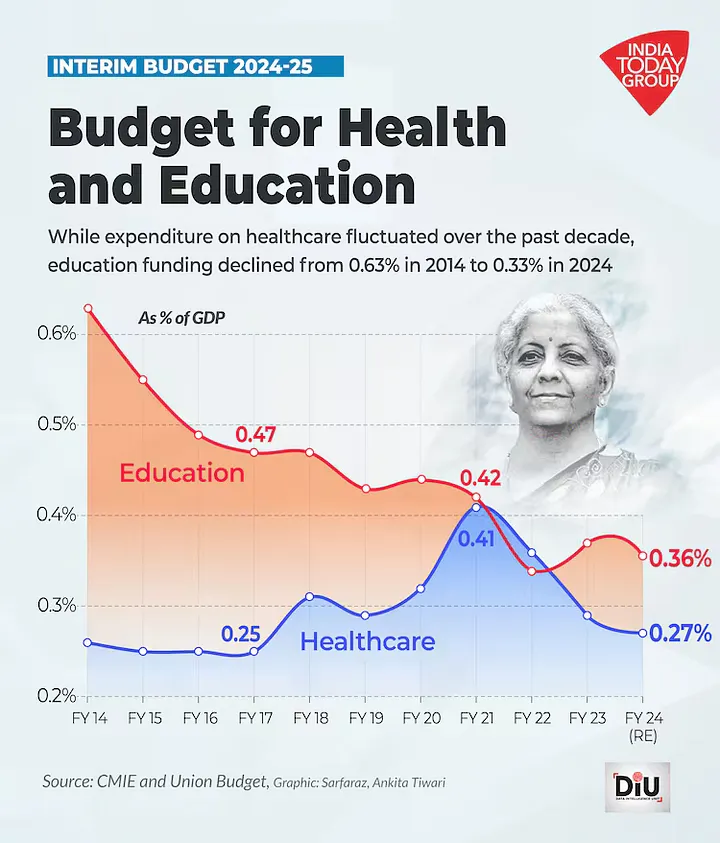

This low allocation reflects the broader issue of declining investment in education. While the absolute figures may be increasing, the percentage of the national budget allocated to education has seen a sharp decline over the past decade. The National Education Commission (Kothari Commission) had recommended that 6% of the GDP be spent on education — a figure also supported by the National Education Policy (NEP) of 2020. However, the current central government’s expenditure on education stands at a mere 0.38% of GDP. The combined share stands anywhere between 3-4% of GDP. With a large youth population and a shrinking education budget, I wonder where we are headed.

In one of the schools, the SMC requested electric fencing. As they tried to describe what it looked like and its purpose, I realized my lack of knowledge made it hard to visualize. In our needs analysis report, we had noted that this area falls within an elephant corridor — elephants often enter houses and raid kitchens in search of grains and food. On the second day, I saw homes located further inland that elephants frequently visit. These homes had fencing: a single line or multiple lines of iron wiring, depending on what families could afford. That’s when I began to grasp the severity of the issue. I was taking pictures as we drove to one of the schools, located just 200 meters from the international border.

By that time, we had crossed multiple rivers in the car. As the heavy monsoon rains hadn’t yet begun, the rivers were not full, allowing us to take shortcuts through the riverbeds. Pranjip told me that all the rivers near the Bhutan border appear black in color. It’s not just the water — the soil has turned black as well. He explained that coal mining in the bordering areas of Bhutan causes the water flowing into India to turn black and become non-potable.

While driving, we also witnessed a police raid and saw a truck seized for carrying illegally mined gravel. We were told that mining is currently banned in the area following an RTI filed by a local individual frustrated by the fact that a single person always won the tender. Since the RTI, mining has been temporarily halted. Now, much of it happens illegally at night, which has caused the prices of both sand and gravel to skyrocket.

We have finally reached the last village, Thulugjhar. It is just a few hundred meters from the Bhutan border. Every house in this village has an electric fence to protect against wild elephants. We sat in the school campus under the shade of a tree and began our conversation with the Head Teacher and the SMC Chairman. They immediately started sharing all their concerns. This is the only school where our construction work hasn’t started yet. The contractor couldn’t find anyone willing to come here due to fears of remoteness, water scarcity, and frequent elephant attacks.

All six schools and their surrounding villages face extreme water scarcity. The ground is rocky with boulders, and groundwater is only found at depths of 250–300 meters. Digging that deep requires heavy machinery, which is expensive, costing lakhs of rupees. With polluted water, dry rivers, and deep underground sources, the water crisis is a major challenge. We installed rainwater harvesting systems with 100-liter capacity tanks in all the schools. While this provides temporary relief during the monsoons, both the villages and the schools need long-term solutions.

As we were discussing, the SMC Chairman pointed to the broken wall of a classroom, sharing their frightening yet strangely light-hearted encounters with elephants. They live in constant fear of being attacked. He told me that an elephant had headbutted the wall last May. The children had left some leftover food from the mid-day meal in the kitchen, and the elephant broke in to steal it. He added that earlier the elephants were scared of the electric fences, but now they run from afar and push through them to enter. The elephants have become more resilient, and the villagers are constantly trying to find new ways to scare them away.

After the incident, another NGO donated an electric fence to the school. While these fences protect them from elephants, there have also been incidents where humans got accidentally trapped in the fences and were injured. The school fence is powered by solar energy due to irregular electricity. The Head Teacher switches it on every evening before leaving the campus.

“Mr. Chandra Mohan Patowary, Assam State’s Forest Minister, in one of his interviews, stated that 1330 elephants died between 2001 and 2022, of which 202 were electrocuted. It is not just elephants — an average of 70 to 80 human lives are also lost annually.”

I had a chance to interact with the masons, and they looked visibly terrified. They are struggling to find water for their basic needs and are spending their nights in fear of elephant attacks. Their motivation is to finish the work quickly and leave.

The school has only one room that accommodates all five classes. The second block, which was used as a kitchen-cum-dining hall, was destroyed by the elephant last year. The village also suffers from severe water shortages. The SMC Chairman shared that under the Jal Jeevan Mission, they had attempted to channel water from a nearby river into a tank. However, the river remains dry for half the year, and the tank was constructed in a location where gravity doesn’t aid water collection. The JJM project has failed, leaving behind unusable infrastructure and persistent water challenges.