“The Next time you come, you’ll have to stay in our homes and not return on the same day ! ” This was the warm request my students from Lyzon Friendship School, Singngat, Manipur made during my last visit to their village — Haijang, almost ten months ago.

The school is part of the School Transformation Program (STP) of Sunbird Trust, the organization I work with. Of the 37 students from the village who attend the school, 29 are supported through sponsorships provided by Sunbird Trust.

Haijang is a picturesque village in the Churachandpur (CCpur) district of Manipur, nestled in the hills of the Singngat subdivision. Home to around 375 people across 50 households, the village belongs to the Kuki tribe, with most families following the Baptist faith. Haijang has a church, a dukaan (shop) and a self-help group, but no school of its own. The nearest school is six kilometers away, which makes the presence of Lyzon Friendship School vital for the children here. Since 2021, the school has been providing a DI Pickup vehicle as transport; before that, students had to walk the entire six kilometers to attend school.

As I slowed my vehicle upon entering the village, I was greeted with a wide smile by one of our students’ parents, waiting by the roadside to welcome me. Her gesture instantly made me feel at home and deeply belonged. She has three children, two studying at Lyzon Friendship School and one serving as a teacher in our school. After sharing a warm cup of tea and a heartfelt conversation at her home, we set out to begin the day’s home visits across the village. Accompanied by our teacher, Miss Chingthem, I looked forward to these visits, a practice I deeply cherish, as they allow me to connect with students and families beyond the classrooms.

At the first home, I found a mother weaving the traditional ponve – a handwoven wrap-around skirt widely worn in Manipur. The ongoing ethnic conflict has disrupted livelihoods, but she continues to weave two pieces a week to sustain her family. Despite the back-breaking work, her commitment to her daughter’s education stood out as a quiet story of resilience. A single parent, she works hard so her daughter can pursue her dream of becoming an air hostess. We spoke about which stream she might choose after Class 10 and which city could be most convenient for her studies.

From there, we made our way to another home where the student’s father greeted us warmly, offering freshly picked gooseberries from their farm. Once a brilliant teacher himself, it was easy to see how his influence had shaped his daughter, who excelled in school.

Our walk through the village then took us to a family connected to Miss Chingthem. Sitting with them, I was reminded again of how the entire village works almost like an extended family, with bonds running deep across households and generations.

By the time evening settled in, we came across a mother returning from the fields, carrying changkongche, a local herb used to make chutney. She insisted on offering it to me, and when I admitted I didn’t know how to prepare it, she promised to make it the next day so I could taste it. Such everyday gestures of kindness and thoughtfulness are what continue to define life in the village.

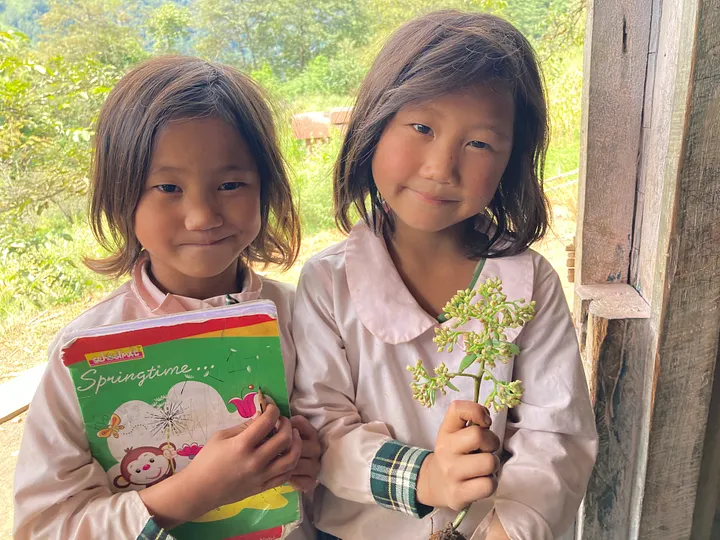

We then began preparing for the much awaited chownein party. Miss Chingthem had sent a student to call all the Lyzonians from the village along with their parents. I had promised the students this gathering earlier, and the excitement in the air was palpable.

That evening, senior boys and girls took charge of the preparations, gently refusing my offers to help. They wanted me to simply enjoy the moment. Soon, students from across the village began arriving with their own spoons and plates, their faces lit with anticipation. It hardly took ten minutes for the entire village’s students to assemble in one home — proof of how quickly word travels here. We sang , laughed and clicked photographs as food was being prepared. Both boys and girls worked side by side: chopping vegetables, boiling noodles and getting everything ready for the chowmein. With every passing minute, the aroma of chowmein grew richer and everyone’s eyes and taste buds were fixed on the steaming pots. The children even taught me a new phrase in the Kuki dialect: “A Tui-e”, which means “the food is tasty.” When the chownein was finally ready, we all sat in groups, each student clutching their spoon. We shared food, conversations, and laughter. It felt like more than just a meal; it was a celebration of togetherness. Afterward, the students cleaned everything up themselves, a quiet reminder of how much they valued community living.

Before the night ended, we took the signature Sunbird group photo where everyone squeezed into the frame, smiling wide. That picture, I know, will remain a lasting memory for years to come.

After dinner, I joined Miss Chingthem’s family, her father, mother and three children, as old photo albums were brought out. We sat together, looking through the albums and sharing stories from the past. I came to know more about the family and the village, since both her parents had grown up here. They spoke of how they met, fell in love, and exchanged letters in their youth. Listening to their stories while flipping through the photographs made me feel like I belonged to their family. That night, I was reminded that places are made beautiful not just by their landscapes, but by the people who live there.

It was indeed a memorable day in Haijang. With all those stories fresh in my mind, I ended the day sleeping at Miss Chingthem’s house, grateful for the warmth of the students, parents and the community.

The next morning, I woke up to the serene green hills of Haijang. By then, Miss Chingthem’s mother and father had already left for their field work. Here, the sun rises early, around 4:00 or 5:00 AM and most people begin their day at the same time, sometimes even earlier if they have to head to the fields.

In Manipur, meals follow a unique rhythm: lunch is usually served between 7:30 and 8:30 in the morning and dinner by 5:00 or 6:00 in the evening. That day, we had our lunch at around 8:00 AM. In local tradition, whenever a guest or well-wisher visits, families prepare meat as a sign of love and respect. Since I follow a vegetarian diet, the family was a little sad they couldn’t prepare such a meal for me. Still, they served a wholesome spread, the vegetables freshly harvested from the farm behind their house. To my delight, another student also brought chankunchey chutney, just as promised the previous day. After this hearty meal, I set out again for home visits, this time joined by my two students.

Our next stop was at our former Head Boy’s house. His mother had gone out for a meeting, so he welcomed us himself. He spoke passionately about village life, self-sustainability and his time in the student council. His communication skills were striking, and our conversation even sparked the idea of conducting a communication workshop for the current student council. His excitement was contagious, and I left feeling proud of his leadership potential. We then headed to another house and decided to return later when the mother was back.

A little further along, we visited the home of three of our students, where their grandmother, Pipi, greeted us warmly. She was over 80, yet her presence carried a gentle strength. We sat and chatted with the family, and to my delight, the Class 9 student asked me a math question he had been struggling with. We worked through it together, and I was glad he felt comfortable enough to seek help outside the classroom. This small moment fulfilled one of my main goals of the visit, encouraging openness and curiosity among students.

Later, we revisited the former Head Boy’s home to meet his mother, a woman of remarkable initiative. She runs a mushroom cultivation project and leads a Self-Help Group (SHG) for women in the village. Together, they produce king chili pickles, bamboo shoot pickles, gooseberry candies, and more, selling them to support their households. She also trains other women in these skills, multiplying the impact across the community. Among all their products, the gooseberry candies and bamboo shoot pickles are my personal favorites. Beyond this, the SHG also provides loans to families who lost breadwinners during the conflict, becoming a quiet safety net in difficult times. Her story reflected the strength and leadership of women in Haijang, shaping their community’s future with resilience. I spent a long time chatting with her, while the former Head Boy shared stories of how his mother used to travel regularly to Imphal before the conflict — learning from the wider community and bringing new ideas back to the village. She has always been an active learner, curious and determined to grow every single day.

By the end of my stay, I had visited every student’s home from Lyzon Friendship School. The warmth I received was overwhelming — vegetables, fruits, gooseberries and home-cooked meals, all offered with genuine love. I realized that happiness in Haijang is built on simplicity. Every household is connected like family, with Sundays spent together in the village church, the heart of their unity. The strength of this community makes life here rich and meaningful.

Sharing life with the families gave me a sense of belonging that no comfort elsewhere could match. As I carried back gooseberry candies, stories, and memories, I knew this was more than just a visit — it was a piece of life in Haijang that I would always carry with me. Staying with the community strengthened my bond with them and left me with memories I will cherish for a lifetime.