It reminded me of something I had once witnessed in real life, something I never thought could exist in 21st-century India. Would you believe that even in 2025, words like slave and master are still spoken, not in fiction, but in the daily lives of people in Arunachal Pradesh? I wouldn’t have believed it myself until I travelled there and heard it from those who live under such bondage.

In August 2021, I was asked to travel to Arunachal Pradesh for a recce visit. Sunbird Trust provides need-based scholarships to schools and students. Whenever a new partner approaches us for support, we conduct an initial assessment to understand the background, context, realities, and challenges of the school and community. At that time, the District Commissioner of East Kameng had suggested a project for Sunbird Trust, so I was asked to visit and submit a report.

I began my journey from Mualdam village and travelled to Seppa, the district headquarters, situated on the banks of the Kameng River. Interestingly, many districts in Arunachal Pradesh are named after rivers. East Kameng is largely inhabited by the Nyishi tribe, who dominate politics, bureaucracy, economy, and land ownership in the district.

I was put up in the old circuit house, which was quite dingy. Coincidentally, the DC was a Telugu officer from Andhra Pradesh. He kindly invited me over for lunch and served biryani, a warm start before what would be a long and intense journey. That evening, I was introduced to the team I would travel with into the interiors.

The next morning, we left for Rawa village with Mr. Ashok Tajo, Mr. Suren, Mr. Momar, and two others. Rawa is one of the remotest Puroik villages accessible by road, though the roads are barely motorable. We set out in three 4×4 vehicles but heavy rains and poor road conditions soon had us stuck. After multiple attempts, we managed to free the vehicles at multiple difficult spots, but at one spot, we had no choice but to abandon one vehicle with the driver and squeeze into the second one to reach Rawa on time.

When we finally reached, Rawa was unlike anything I had ever seen. The village sits on a cliff draped in clouds. There is no phone network, no electricity, no proper roads, no shops, and almost no government presence. The houses are small, single-room wooden huts with roofs made of dry leaves and tin.

Despite these harsh conditions, the villagers welcomed us warmly. They served us hot food and lit a fire to help us dry our rain-soaked clothes. For the first time, I was offered food made from sago palm instead of rice, which is usually the staple across Northeast India. The Puroiks grind the bark of the tree into flour and prepare a dish called Rangbang. I was excited as I was getting to experience many news.

Rawa and the surrounding villages do not have private schools, and the only government school in the village is effectively defunct, the teachers, mostly from the Nyishi tribe, rarely attend. As a result, most Puroik children remain out of school.

When we met the parents, we asked if they would consider sending their children to Seppa, should a hostel facility be established at minimal cost. They readily agreed, saying this would at least keep their children safe from the reach of their “masters.” After a long discussion, we left for Chayangtajo, where we stayed overnight.

The next day, we visited Sangchu, another Puroik village. Village heads from nearby settlements gathered there to meet us. Parents again expressed their desire to send their children to Seppa, hoping education could shield them from exploitation. Some villagers even shared painful accounts of children being abducted by their masters. One man described how one of his cousins’ heads was shaved and blackened because he had mistakenly cut a tree on Nyishi-owned land. Their stories revealed oppression and fear.

The Puroiks are a hill tribe of Arunachal Pradesh, found across 50+ villages in districts like Subansiri, Upper Subansiri, Papumpare, Kurung Kumey, and East Kameng. Their population is estimated at around 8,000. They are at a transitional stage between a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and agriculturalism, they now farm small plots and collect forest produce. The majority still follow their traditional faith, Donyi-Polo (worship of the Sun and Moon), with a few converting into Christianity. Their identity is also visible in their attire, men typically carry a long chopping knife and wear a distinctive cloth across their chest and thigh.

The Puroiks were derogatorily called Sulung, meaning “slave,” by the neighbouring Nyishi (Bangni) community. Oral history suggests that generations ago, their forefathers borrowed money from the Nyishis and, unable to repay, became bonded labourers. Over time, this arrangement evolved into a rigid social structure where Nyishis assumed the role of masters and Puroiks were treated as slaves.

Every Puroik family has an owner who decides their fate. Since time immemorial, they have been farming for their masters. When a Puroik man gets married, he is expected to serve Mithun at the wedding feast. Unable to afford the high cost, many borrow from their masters — forcing not only themselves but also their wives and future children into bondage. This cycle of debt and servitude has continued for generations. Although slavery was officially abolished in 1976, reports suggest that exploitative practices still persist in some areas even today.

In recent years, the Arunachal Pradesh government has tried to uplift the Puroiks. In 2017, it established the Puroik Welfare Board. But social, political, and economic suppression still weighs on the community.

During my visit, the then District Commissioner, along with Mr. Ashok Tajo, an educated Nyishi man, recognized that education could be the most effective tool to break this cycle of bondage. We decided to propose a hostel facility at Seppa to house Puroik children and enroll them in local schools. Unfortunately, before the project could take shape, the DC was transferred, and the plan never saw the light.

https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/special-report/story/19831031-sulungs-of-arunachal-pradesh-saga-of-an-innocent-tribes-inbuilt-resistance-to-change-771162-2013-07-15

When I asked why he chose to start a school for Puroik children, he replied, “I know the Puroiks very well. They are also at fault in some ways — whenever they don’t have money, they immediately run to their masters for help. I am a Nyishi myself, living in Seppa and working in a government department, and I’ve seen this practice since childhood. Unless strong, educated leaders rise from within the community, they will always return to their masters, no matter what the government does.”

He then shared his personal struggle: “Last year, I enrolled a few students in a government upper primary school in Lapung. But the teachers were absent most of the time and rarely took classes. I wrote a letter to the DDSE (Deputy Director of School Education), and their salaries were stopped. The teachers and their families blamed me and verbally attacked me for that. I was on the verge of giving up. That’s when I met an NGO willing to support me. With their help, we started a school this year in a rented building. We recruited a few teachers and began running it properly. Now, I am planning to take voluntary retirement from government service to dedicate myself fully to this school. I feel this is my true calling.”

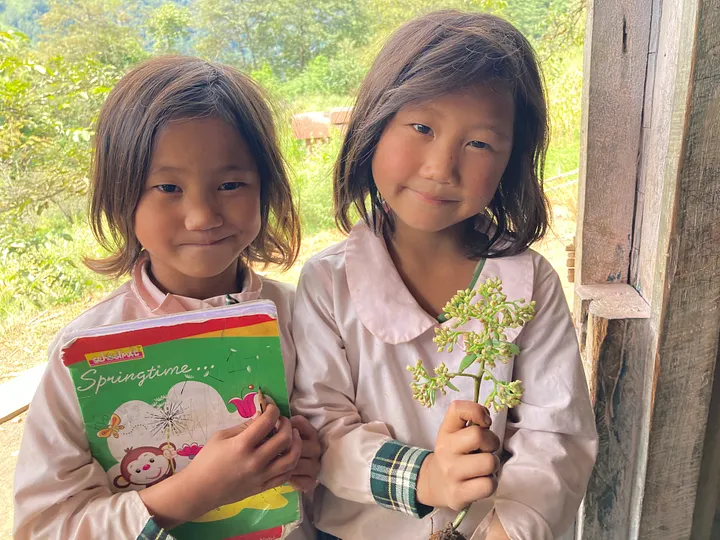

Today, Mr. Agung runs a school for 46 Puroik children in Bana Valley. It may be a small beginning, but it carries immense hope. Perhaps, with education, these children will grow up not as slaves but as free individuals — able to claim their rights and chart their own futures.